If you watch C-SPAN for even a few minutes you may notice that many of the U.S. Congress members are on the older side. Dig a little deeper and you'll find that many of them didn't have gray hair when they first took their oath of office. Rep. John Dingell, a Democrat from Michigan, served almost two-thirds of his life in Congress — 59 years — before his death at age 92 in 2019.

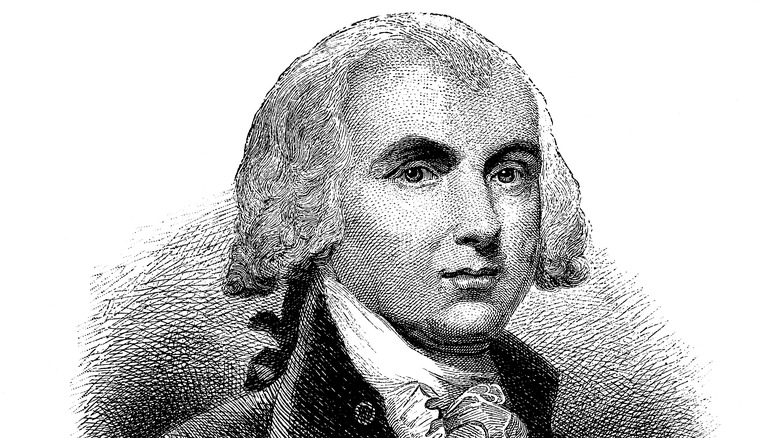

The reason Dingell and many other long-serving Congress members — including Sen. Diane Feinstein, who served nearly 31 years before her death on September 28, 2023 — are able to do this is because of the U.S. Constitution. James Madison, the fourth U.S. president who is known as the Father of the Constitution, pushed hard to prevent term limits and got his way. The U.S. Supreme Court also helped by shutting down the more than 20 states that had instituted term limits for their Congress members in the 1990s.

Why didn't James Madison want term limits for members of Congress, especially since he and the other delegates to the Continental Congress — the precursor to today's governing body — have them? Members of the Continental Congress couldn't serve "more than three years in any term of six years," per the Articles of Confederation. Madison and his followers believed that the longer a person served, the more experience they would gain and the less likely they would be "to fall into the snares that may be laid before them," as he wrote in the Federalist Papers.

The thinking was that elections were a better antidote to potential corruption than term limits. Seasoned senators and representatives, it was thought, would be able to handle the day-to-day job of governing better than newbies who might leave it up to staff or lobbyists, per the Congressional Research Service. In the end, the Constitution did not set any term limits.

In the 1990s, 23 states tried imposing term limits on the senators and representatives they sent to Congress. In 1995, the issue came before the U.S. Supreme Court after Arkansas attempted to set the limit for U.S. representatives to three terms and senators to two terms. The League of Women Voters brought the case to the court, and in a 5-4 decision, the court determined that states did not have the right to set term limits.

"Such a state-imposed restriction is contrary to the 'fundamental principle of our representative democracy,' embodied in the Constitution, that 'the people should choose whom they please to govern them,'" Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the majority. "Allowing individual States to adopt their own qualifications for congressional service would be inconsistent with the Framers' vision of a uniform National Legislature representing the people of the United States." The decision meant that only a constitutional amendment could impose term limits. So far, that has not come to pass.